Folks using screen readers and anyone who prefers to listen — there’s an audio player bar just below this paragraph, with a play button on the far right. Please let me know if you have any trouble with it.

I started out on my lifelong journey as a patient just after my first birthday. Some of my earliest memories are of my doctor squinting at my x-rays, getting out his little measuring contraptions and drawing lines across the bright-white image of my bones, jotting down numbers next to the escalating curve of my trunk – every 6 months for years – tracking the precise pace of its collapse.

I would sit on the exam cot, the paper crinkling beneath me every time I stirred, as my doctor talked quickly and softly into his small tape recorder – the language streaming out of his mouth indecipherable, extraterrestrial, clinical. These words weren’t for me, or even for my parents, but for his secretary to type up in Courier New, print onto paper with perforated edges, and slip into the growing collections of pages in my medical chart. A body documented. Cataloged. Filed.

Several decades later, well into my 30s, I spent an afternoon hanging out with a group of disabled teenagers at a summer day camp. I wanted so much to create a safe space for them to process freely what this experience – being young and disabled – was like for them. What felt urgent, funny, painful, light, impossible? What questions did they have for someone a little bit further down the road?

I’m often eager to dive headfirst into the very bone marrow of the thing without knowing someone terribly well, which is its own whole topic for therapy and surely played some part of what happened next – when I opened up the space for us to talk about experiences of disability, most of these kids recited their diagnoses, surgery dates, the mobility aids they use and when they started. It was as if all of the human vibrations I’d already felt thrumming out of their smile lines while they talked about Mario Kart and Taylor Swift had been sucked out of the room in one sweeping vacuum seal. Suddenly, we were in a sterile clinic. I could almost hear the tissue paper crinkling as we wiggled onto exam cots. And once I heard their stories of disability, I immediately recognized the script. It was the same one I learned under the fluorescent lights of medical spaces – one of the only scripts I’d been given for understanding my body. (**Sidenote: read to the bottom of this essay to peek at the project that started when I got home from this sweet afternoon I spent with these rad teenagers.)

Growing up, whenever anyone asked me about my wheelchair – which was often, I mean, hello curious world, here I am, a visibly-disabled young person with a blazing spotlight beaming across my body, here to answer all your invasive questions until your voracious inquisitiveness is satiated – I was ready with The Story. I was diagnosed with cancer on my spine when I was 14 months old, at first an astrocytoma, then they found a ganglioglioma, and blah-blah-blah medical jargon, boopety-doop medical treatments, yee-haw surgery dates. I can do thises and thats but not those and theses. And so it went.

For so many of us with disabled bodies/minds, the only language we learn to describe our experience of disability comes from healthcare systems. So often, we come to understand our personal, individual, layered lives through narrow, prescriptive, linear arcs – sickness/injury → treatment/intervention/assistive devices → fixed/unfixed. There are no built-in checkpoints to make sure we also hear stories about the long, grueling, thrilling fight for disability rights or the vibrancy of disability solidarity or culture. It’s rare to stumble onto narratives of disability love, joy, parenthood, professional success, friendship, artistry even in 2024, and in the entirety of the 90s only six people in all the world happened to find one of those stories by accident. (This is an estimate. Upon further reflection, I think the number might be lower.) The point is, many of us survive sick and disabled childhoods without ever witnessing a disability narrative that lives outside of the medical arena. And without words, giant swaths of our experience remain locked in the narratives of interlopers.

And even if we are lucky enough to learn new words and hear new stories, it can be difficult to rewrite the scripts we’ve learned, often before we even had language. In fact, well into my 30s, after years of reading disability studies and writing a whole book exploring the nuanced human stories of disability far outside the medical paradigm, I found myself speaking to a group of adults who worked for a company interested in understanding disability through a more critical, thoughtful lens. This business was all about play for children, and so, to start off the conversation, the moderator asked me to give a brief recap of my childhood and how disability became a part of my life. Without pause, I launched into the script I’d learned as a child – When I was 14 months old I was diagnosed with cancer on my spine and so the story goes. When I wrapped up my medical origin story, the moderator paused, then mentioned to the audience that disabled people don’t owe anyone their medical history. I felt like I had just flashed the audience. Why had I reached so quickly for that old medical script? After all the learning and writing and reclaiming. Still?

The older I get, the more I realize that only so much of the work can be done inside my head. How do I sneak past that cerebral membrane and reach that lump in my throat, that twist in my gut, that tensing in my shoulders?

A few months ago, my mom gave me a tub of artifacts from the past – old photo albums, newspaper clippings, and, perhaps most interesting to me at this time in my life, medical charts from my early childhood. I recognized the Courier New font, words like “specimen” and “anaplastic” and “anterior-posterior fusion.” Young Rebekah, the medical curiosity, the sample of tissue to flatten onto a slide for further study. Is it possible to find a living human in these documents – the warm body, breathing-in-and-out Me? I’m so curious about her, but I don’t know how to find her. It’s hard not to look for clues in the artifacts that were collected around her in these formative years.

I’ve long been intimidated by poetry, but when I started teaching high school English, it felt like the time had come in which to dip my toes. We started with blackout poetry. (Sometimes referred to as erasure poetry or found poetry.) This kind of poetry is made from text that is already printed. The only job of the poet is to grip their permanent marker, block out the words that aren’t essential and wait to discover what is already there, waiting to be seen. I loved the way this practice was so accessible – the way it felt more like the poems found you than the other way around. Everyone could be a poet! I’ve always been impressed by the way Kate Baer uses the medium as reclamation and conversation, especially with those misogynistic messages that creep into her DMs. But it wasn’t until this year, riffling through these documents, I wondered – what would it be like to reclaim a narrative within my medical charts? Could I pull a human story out of clinical notes? Could I find a living piece of myself there?

I made copies of the hospital documents, pulled out a fresh permanent marker, and waited to see what story wanted to be told. What tiny bit of human life might peek its face out between the jargon?

If you would like to experiment with this form of story reclamation, too, the basic steps I follow include scanning the document, circling words/phrases that stand out, making a list of those words in the margins, and crossing out more and more words until a single idea emerges. Then – the most satisfying bit – black out every other part of the page until only your chosen words remain.

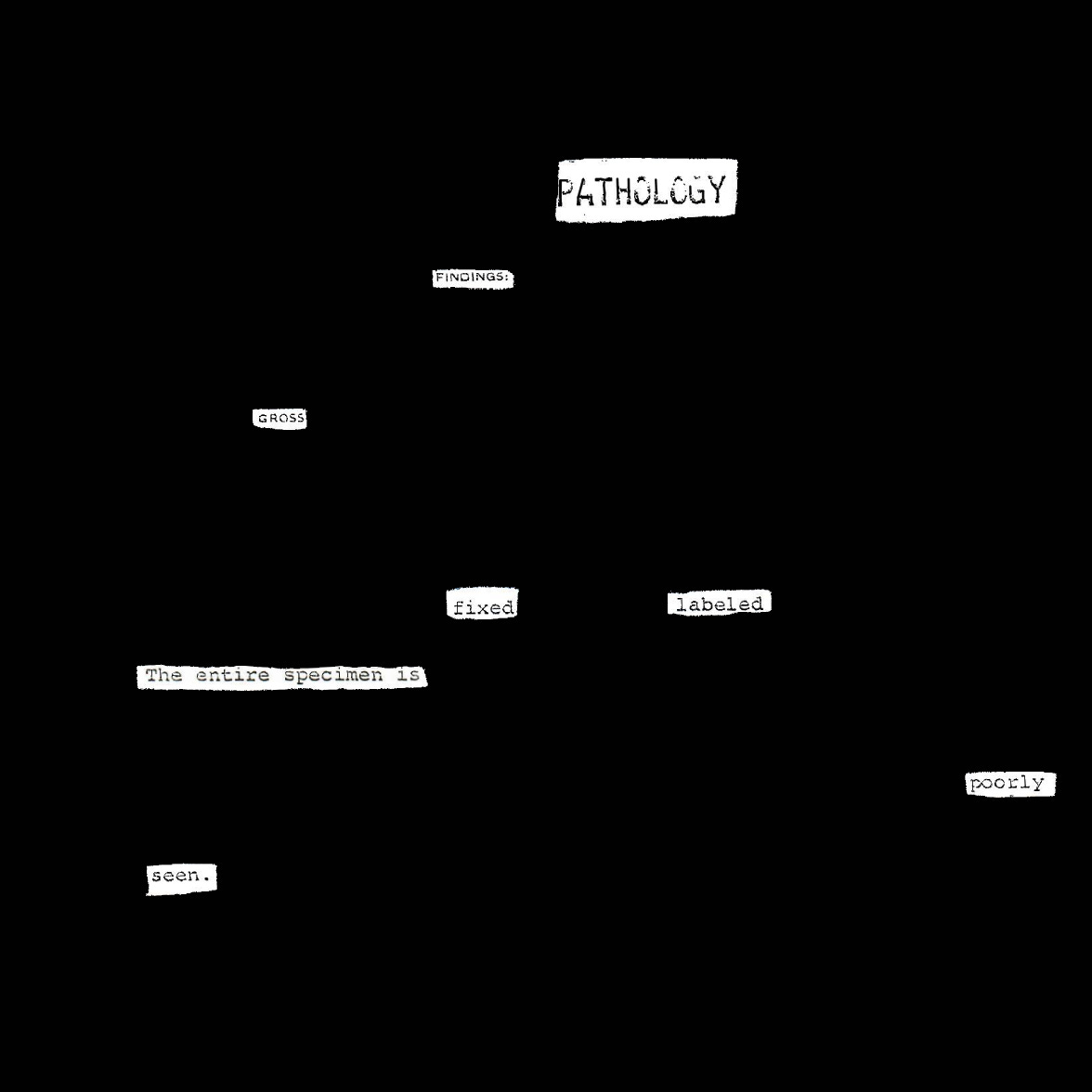

The first document I picked up was the pathology report describing the malignant tumor discovered in my baby spine. It includes a diagnosis section, a “gross description,” and a “microscopic examination” with measurements and colors of the tumor. It includes words like “vesicular nuclei” and “cystoplasm.” Some of these words would appear again and again in future medical documentation, words medical professionals would glance over before ever looking at my face. This is the poem I found hiding in the jargon:

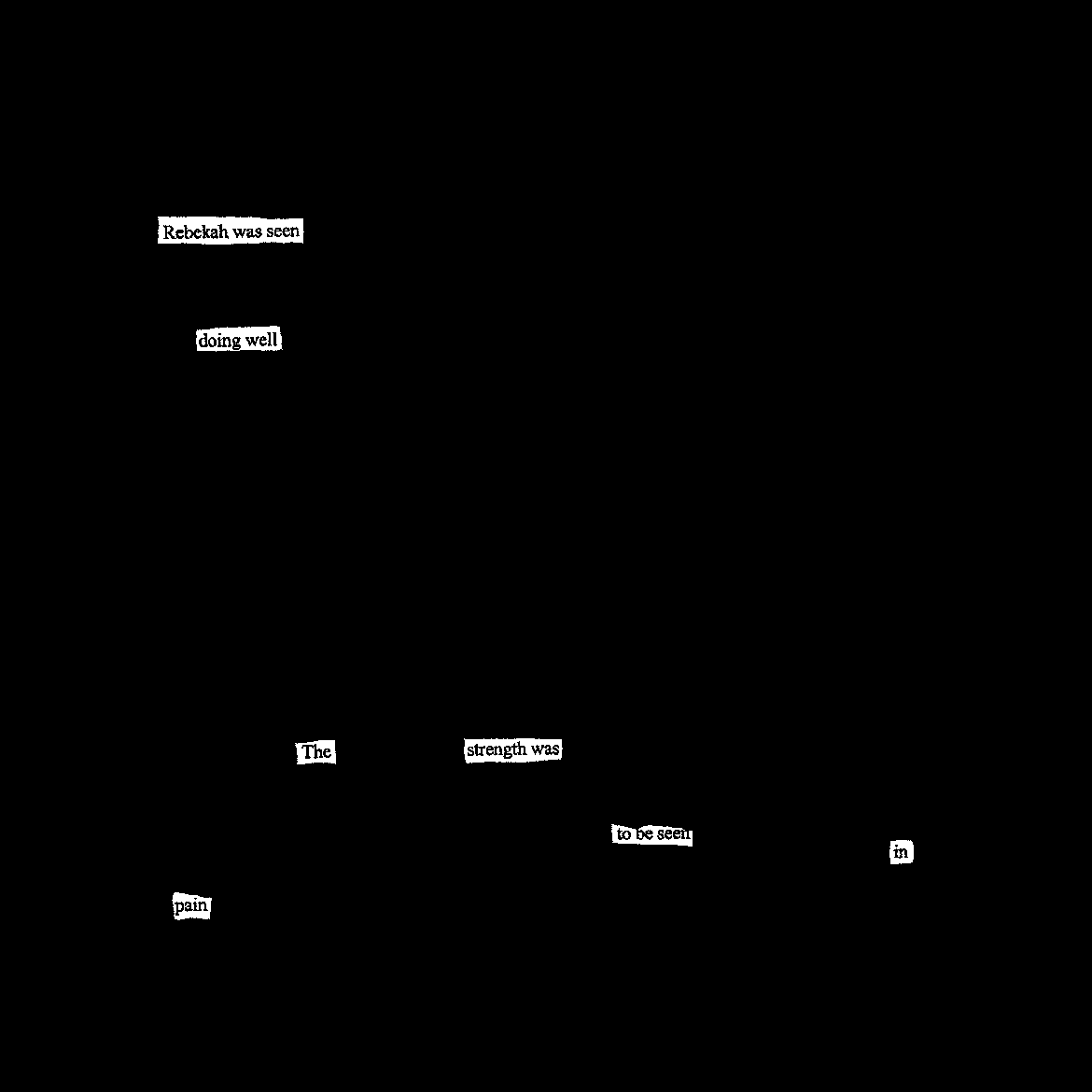

The second and third documents I copied were reports written during my late-teens. By this point in my life, I was exerting every cell of energy into keeping up and shining bright and making sure the whole world knew, I’m fine! Great, actually! Everything is great!, even as the cracks in my inner-world were deepening. Even as I couldn’t bring myself to get out of my car at the end of the day. Even as I fantasized about disappearing. Some phrases I find most interesting in these documents include “The patient has been very active,” and “She does complain of extreme fatigue,” and “She was cheerful and friendly.” Along with lots of fun descriptors like, “abnormal gait,” “spastic paraparesis” and “hyperreflexia.”

This is the poem I found tucked into the second document:

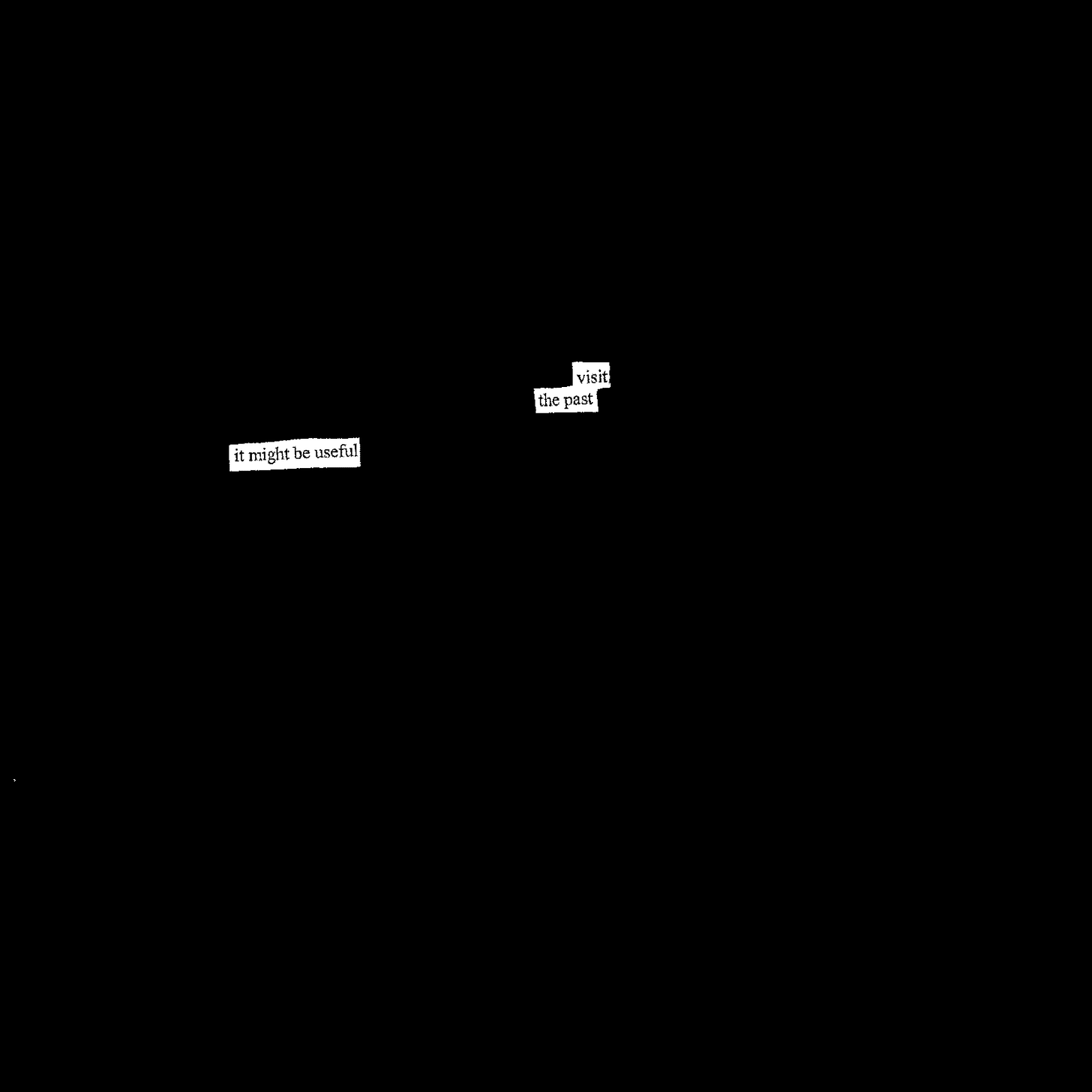

This is the poem I found buried in the third of these medical documents:

I felt relief swiping out whole paragraphs from these documents – my ink dark and in charge, bleeding over the words that had always been written over my body, obscuring the twinkle-ache in my real eyes blinking under fluorescent lights. I felt delight when the remaining words clicked into place – there is something else we want to say – something else to be seen/heard here!

I do understand the original purpose of these documents. I do realize that this medical system is the very same one that cut and burned and poisoned the cancer out of my body so that I could live. I even believe that most of the healthcare folks I’ve worked with across my life have cared about me as a human. In fact, the same doctor I described at the top of this essay as squinting at my toddler x-rays sent me a wedding present when I got married at 22, and when he heard about my divorce a year later, he sent me a short, heartfelt note that ended with the words “It’s better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all.” And yes, I’m pretty sure we all know he sent a voice memo to his secretary to send that message to me, but none of it was a requirement of his job, and it still means a great deal to me that he was paying attention to the turns my life took as I became an adult.

And also. There is something about the practice of medicine that seems to make it difficult for the spirit of a human to remain alive, intact. Or, there aren’t enough practices in place to counterbalance the crushing machine of medical systems. Or, this whole world is harsh, and it’s very hard to remain human when no one is there to remind you how to do it or why it’s important. I am looking for tools, for scripts, yes, maybe even tricks to remind my body she’s here, and I am listening.

In the spirit of rewriting medical histories, I wanted to give you a peek into the project I started when I got home from hanging out with the group of disabled teenagers at the summer day camp. I couldn’t stop thinking about that lonely, medicalized experience of disability I’d known as a kid, especially in contrast to the vibrant experience of disability solidarity and friendship, culture and history I’ve experienced as an adult. So I set out to write a poem – an invitation – a sort of anthem to instill a sense of pride and belonging in the experience of disability.

As I searched for words to describe an experience as deep and wide as disability, I thought about the endless mismatching between a disabled body/mind and the world as it’s been arranged. And in that sprawling, textured experience of embodied mismatch, I marveled over the fact that we continue to exist. We’re here – making jokes and stories and friends and families and plans and quilts. We’re cuddling and crying and taking deep breaths and watching the clouds and challenging the status quo with our mere existence.

That, to me, is solid gold scrappiness – the kind that ran through my limbs as I intuitively found ways to move my newly paralyzed body, buoyed me enough to let me grieve the hardest parts of disability, and brought me joy. So, I wrote a poem that started with a tiny set of words to instill pride & belonging within disability – “We are the scrappy ones.” Over the next three years, that poem evolved into a picture book, and the first line of that poem became its title.

As I honed the words for these pages, I thought of them as a sort of song to remind us of our inherent value, just as we are. I wanted to dispel deep, old myths that still rest on our shoulders – we are not a burden. Our lives lead to life in abundance, our existence gives us the building blocks to home. Our stories are not any one thing – our endless variety is part of our strength. I wanted to point to a larger history – to show readers the faces of revolutionaries whose fight has always been for us – whose legacy we are a part of. Kirbi Fagan set to work illustrating these words into faces, friendships, and hot air balloons – a whole world.

We Are the Scrappy Ones is now available for pre-order, and I know you know how important that pre-order piece is to the life of a book. I hope these pages make their way into so many laps, libraries, bookshelves, and families. If you have the means, it’s now available at all the big book-publishing places.

HOWEVER, if you want a signed copy of the book AND want to support the coziest local bookshop, I’ve added the pre-order link offered through one of our all-time favorite spots, Monstera’s Books. And just so you know who you’d be supporting, let me tell you this shop is run by amazing humans who value reading and books and community and plants!

CHEWY QUESTIONS – If you want to continue to think through the ideas here, these questions are for you – please feel free to explore this in your personal writing, to talk about it with your people, or to join the conversation on Substack.

Have you found tools, scripts, yes, even tricks to stay human – have you found ways to tune out the words written/spoken over your body/mind and tune into your own voice – amidst the dehumanization built into the systems around you?

If you do end up making your own blackout/erasure/found poems, would you want to share about your experience of it here? Medical charts are one thing, but I’m also thinking about text messages, tweets, messages in comment sections, articles, press releases, transcripts of political speeches, journal entries from a past life, song lyrics – anything you want to speak back to, rework, rewrite, push against. I wonder what words might catch your eye/ear as you scan the narrative. What is peeking back at you, waiting to be seen?

Thank you for being here.

xo

Rebekah

/ the entire specimen is poorly seen /

God, what staggering truth. The nuanced, visceral, spectral rewriting of your story has been and continues to be a gift for us all Rebekah. ❤️

I struggle to find words to express how it feels to read your words. They always sink directly into my heart. Today I just want to say that I am very grateful for you, and for your incredible ability to not only sort through these things, but also to write them out in such thoughtful, compassionate, and meaningful ways. Thank you for being willing to share these pieces of your story with us, and for helping guide us as we navigate these things too <3 I like your idea of reclaiming stories with blackout poetry. I think I might try this with some old journal entries. AND Congrats on the book!! I know it will be a gift to so many.